Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell just announced another quarter-point interest rate hike. The markets immediately responded by dropping several hundred points.

In his arrogant and smug statement, Mr. Powell told us that the economy needed higher interest rates. How does he know? Well, in fact, he doesn’t know. The interest rate is nothing more than the price of money over time.

For at least a couple of thousand years, certain members of the political class have asserted they know better than markets what any price should be. Mankind has a long and dismal history with government price controls. They always fail. If the price for anything is set too low, markets refuse to provide it. Venezuela has price controls of toilet paper — hence no toilet paper.

If you are old enough, you may remember President Jimmy Carter thought the price of gasoline was too high (after the Arab oil embargo) so his administration set the price and the quantity you could buy at any one time. The result — endless gas lines that burned fuel unnecessarily and caused tempers to flare.

If the price is set too high, there will be surplus. The City of Baltimore has just announced a gun buy-back program, where they will not only buy guns but also ammunition clips. Two problems: Such programs always fail to reduce the number of guns used in crime, and the good folks in Baltimore have offered to buy some gun clips at a higher price than some retailers sell them for. It does not take a rocket scientist living in Baltimore to figure out that he or she can make a tidy profit by buying clips and then selling them to the city.

The folks at the Fed may have a more extensive vocabulary but, in fact, they make no more sense than the Baltimore City Council or the whiz kids of the Carter administration. The Fed folks claim they have to bring interest rates up to “normal” to prevent inflation.

A market-determined interest rate would be determined by the supply and demand for investible funds — and that rate varies over time due to local and global economic conditions, changes in productivity and the age structure of the population. There is no fixed “normal.”

In order to target inflation, the government needs to be able to measure inflation with a fair degree of precision and accurately forecast future inflation. The ability of the Fed and other government agencies to do this is actually declining rather than getting better over time — because of increasingly rapid technological change. Changes in prices of the necessities of life, such as food, are easier to measure over time than changes in prices of discretionary items, such as most services and tech devices.

The U.S. government claims that consumer price inflation is running about 2.2 percent. But that number does not fully capture the endless improvement in goods and services we consume and the substitution that everyone does when the price of one product rises relative to another close substitute.

The software providers for my desktop computer, tablet and smartphone send me and everyone else frequent updates. These updates often make my device work better and add features that I did not originally buy — so, in effect, all of us are receiving continuing price reductions for many of the products we own.

Apple and many other companies receive the bulk of their revenue from products that did not exist 15 years ago, but often are very different and better substitutes for things that most people no longer want. The fact is the skilled people in the government agencies who are trying to measure all of the variables in goods and services that determine the level of “inflation” do not have the knowledge or tools to do so. To rely on such numbers to determine the “appropriate” interest rate is a fool’s errand.

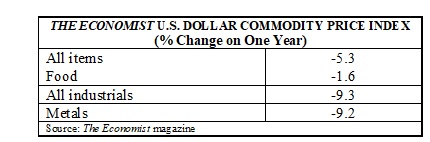

However, commodity markets do provide accurate and long-term measures of changes in price level. For instance, the price of a bushel of wheat or corn, or a ton of copper in U.S. dollars has been known for a couple of centuries.

The items that can be measured accurately (commodities) are falling in price (deflation). The items that cannot be measured accurately appear to be rising slightly in price. The Fed says its goal is 2 percent inflation — even though the Federal Reserve Act says they should seek price stability (zero inflation?).

Fed Chairman Powell said his goal is 2.5 percent real growth. Why not 4 percent? There are many economists with better track records than the Fed — including yours truly — who believe that with the appropriate fiscal policies, 3 percent to 4 percent real growth is possible without inflation. A non-market determined interest rate (by Fed) that is set too high will depress growth. So, Chairman Powell seeks to provide a self-fulfilling prophecy, which will make millions of Americans poorer than they need be.

The good news is the rise in global crypto and commodity-backed digital currencies will sooner rather than later drive the Fed out of it fool’s errand of attempting to set interest rates.

Richard W. Rahn is chairman of the Institute for Global Economic Growth and Improbable Success Productions

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/dec/24/why-the-federal-reserves-setting-of-interest-rates/

© Copyright 2018 The Washington Times, LLC.