What happens to a family whose yearly spending rises faster than its income? A painful day of reckoning arrives, requiring drastic cuts in its spending or a declaration of bankruptcy. What happens to a business whose debt burden grows to the point where the interest payments on the debt impede the ability of the business to continue?

The business declares bankruptcy, restructures or both, and normally the managers’ incomes are cut or they are replaced. What happens when a government has reached the point of diminishing returns from taxes, increasing its debt and necessary interest payments to the point where it can no longer provide essential services? The population suffers from the cuts in government services and the stifling tax burden — while those politicians and bureaucrats that caused the mess continue to suck at the teat of government.

Government officials in the U.S. and most other rich countries have been spending taxpayers’ money as if it were play money in a child’s game, with no limit to what can be borrowed. The negative effects of all of this added debt have been hidden through the artificial suppression of interest rates — making the spending binge appear to be almost costless. But then reality struck with the big rise in inflation — caused by a supply shock (lack of goods) from the pandemic shutdowns and from the explosion in money growth (new money was being printed far faster than the increase in production of goods and services).

The rise in inflation has forced the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates. The interest rate rise causes all borrowing to be more expensive, including what the U.S. Treasury needs to sell government bonds — greatly increasing government outlays without the benefit of added government services. Larger interest payments, coupled with either higher taxes or more debt, lead to a fiscal death spiral.

As an analogy, many people take on more debt than they can comfortably manage, which causes them to go deeper into debt merely to pay the interest on the debt they have already incurred. Ultimately, it forces them to also reduce their spending on goods and services. When this happens to large numbers of people at the same time, it reduces the growth in total spending, leading to a recession.

Businesses are also suffering both from reduced consumer spending and from an increase in the interest paid on their debt, reducing their ability and incentives to engage in new capital spending and hire more people, further depressing productivity as well as growth of the gross domestic product.

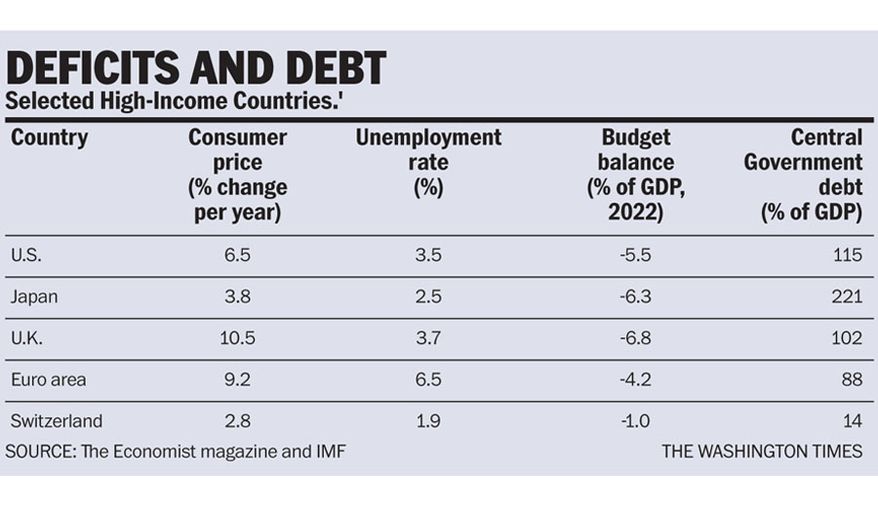

As can be seen in the enclosed table, almost all governments of the large rich countries have increased their debt burdens to levels close to or exceeding their GDP. Debt is near the level when the fiscal death spiral has or is likely to begin.

The initial surge in inflation is likely to moderate for some months as the supply shortages disappear from more production and less demand, but the underlying fiscal problem remains, leading to more deficit spending, which will result in a renewal or at least steady inflation at an elevated rate. Over time, inflation reduces the real value of the government debt until it reaches a manageable level.

For example, assume you have a $100,000 interest-only mortgage on your home. Also assume that you earn $50,000 per year, and that your salary just keeps up with the rate of inflation for the next 10 years. If the rate of inflation averages 7% per year, 10 years from now you will be earning $100,000 per year yet have the buying power of only $50,000 today. But your $100,000 mortgage will be equal to a $50,000 liability in today’s dollars.

Most of the former communist countries in Eastern Europe have low and manageable debt-to-GDP ratios because they suffered very high rates of inflation during the economic transition 30 years ago on which, in some cases, made them almost debt free. The higher the rate of inflation, the quicker the real value of the government debt erodes to manageable levels.

The current fiscal disaster will be self-correcting as described above, even if nothing is done — but the people will lose the real value of their social security and other government payments causing great hardship, even though there is no reduction in the nominal payments. Given that tax revenues are still running at a rate about eleven times higher than interest payments, the government can still pay interest and principal on the debt as well as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid for many years.

A default on the required debt payments will occur only if Congress and the administration refuse to cut other spending.

Rather than fight about specific spending cuts in the next two months (which are likely to be very small at best), it might be wiser to demand spending process reform. Two decades ago, the Swiss reformed their system to require a balanced budget over the business cycle, known as the “Swiss debt brake.” It has worked very well, as can be seen in the table, and is fiscally responsible. Congress should try a similar system in the U.S.

• Richard W. Rahn is chairman of the Institute for Global Economic Growth and MCon LLC.

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2023/jan/23/debt-deficits-and-default-us-should-consider-swiss/

© Copyright 2023 The Washington Times, LLC.